The Peril of Power when Prioritizing a Point Estimate

I recently noticed that the Pfizer immunobridging trials, presumably set up to demonstrate that their COVID-19 vaccines elicit the same antibody response in children as was seen in 16-25 year olds, for whom efficacy has previously been demonstrated, have a strange criteria for “success”.

GMT: geometric mean titer. This is a measure of the antibody titers. We use the geometric mean because this data is quite skewed (it is also why you typically see it plotted on the log scale). For those of you who ❤️ math, the equation for the geometric mean is just \(\exp\{\frac{\sum_{i=1}^n\textrm{log}(x_i)}{n}\}\)

The primary endpoint of these trials is geomteric mean titer ratio, that is, the ratio between the geometric mean antibody concentration in the younger age groups compared to the 16-25 year olds’ geometric mean antibody concentration.

According to the recent write-up from the 5-11 trial in the New England Journal of Medicine, the trials have been set with two measures of success:

- The lower bound of the GMT ratio must be \(\ge 0.67\)

- The point estimate of the GMT ratio must be \(\ge 1\)

The second criteria was originally set by Pfizer to require that the point estimate of the GMT ratio must be \(\ge 0.8\), however after their data lock the FDA requested this to be changed to the higher threshold. While at first glance, this may seem to make sense, after all we often want to make sure that we hold our pediatric trials to a high standard of efficacy, it turns out this change has statistical implications that change the target in ways that are non-standard for non-inferiority trials.

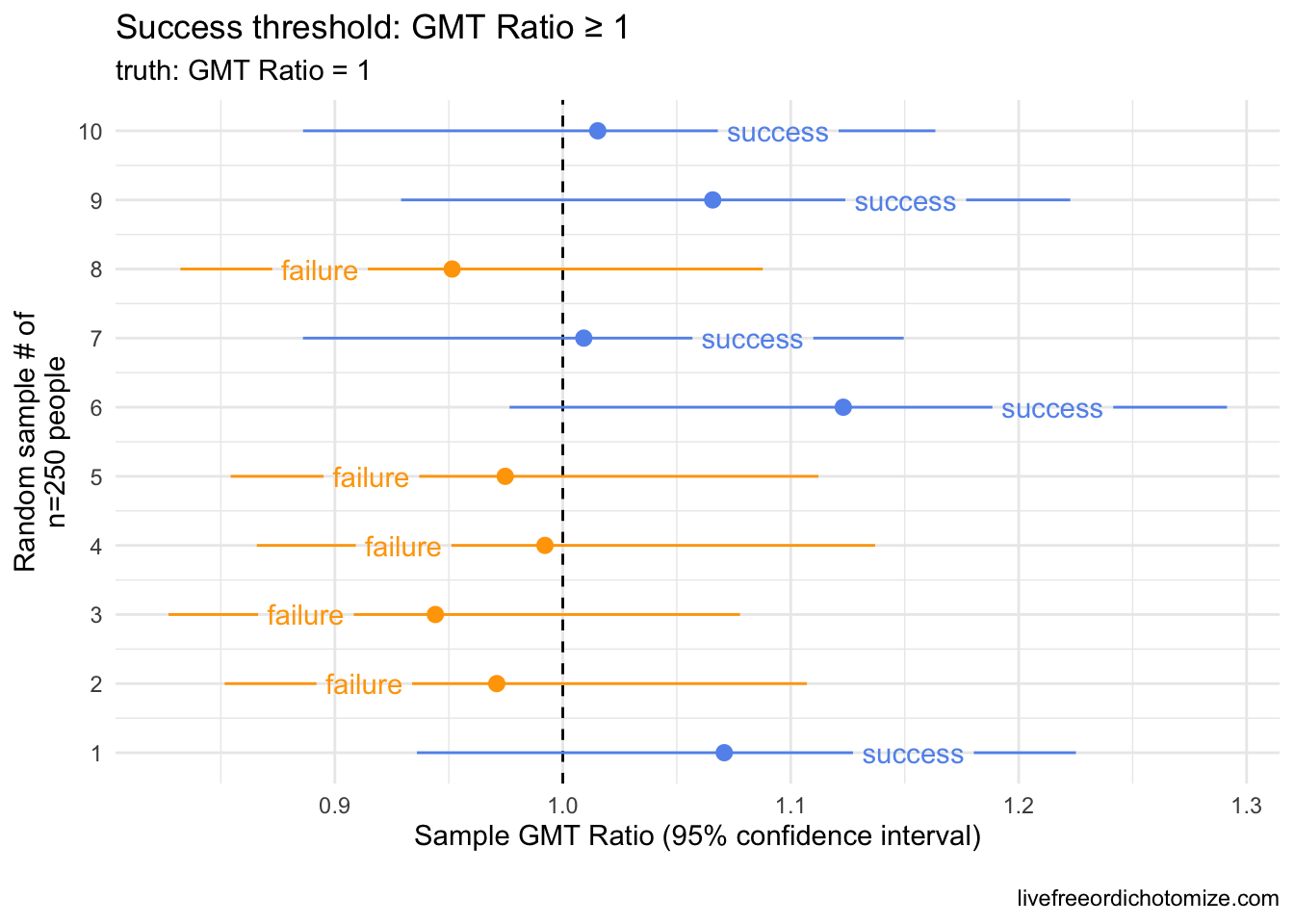

What do I mean? If we believe that the distribution of antibody concentration in children is exactly the same as what we observed in 16-25 year olds, we would expect this second criteria to fail 50% of the time. Why? When doing any trial, we are observing a sample, not the whole population. We expect a certain amount of uncertainty in our estimates. Here is a small example. Below I have generated 10 samples of 250 people from a log normal distribution with a mean of 1142.5 (log mean of 7.04) and a log standard deviation of 0.8. I am comparing this to an observed sample of 253 individuals drawn from the exact same distribution (incidentally, there were 253 16-25 year olds that led to the “benchmark” of a geometric mean of 1142.5).

Want to try it yourself? You can generate samples from a lognormal distribution in R like this rlnorm(253, mean = 7.040974, sd = 0.8). You can then compare the geometric mean ratio across several samples generated from the same distribution.

Notice in the above plot that even though the true GMT ratio between these groups should be 1 (they were drawn from the exact same distribution!), when using the point estimate as the threshold for success, we “failed” 50% of the time. It was a coin toss whether this trial succeeded or failed by this criteria.

The standard error is just the {standard devation} divided by the square-root of the sample size, \(n\), \(\frac{sd}{\sqrt{n}}\)

This may not be completely intuitive at first glance, but in fact we can show that the probability of “succeeding” under this criteria is driven by how much better the antibody concentration is in children compared to the benchmark – it is linked to the standard error.

This standard error multiplier is just the critical value derived from a standard normal distribution at a given quantile. You can calculate any success probability in R using the qnorm() function. For example, if we wanted to know the standard error multiplier we’d need to have at least a 70% chance of succeeding by this criteria, you would run qnorm(0.7), revealing we’d need to be at least \(0.52 \times \textrm{standard errors}\) better than the target.

In order to have a probability of success greater than 80%, for example, the childrens’ antibody response would need to be at least \(0.84 \times\) standard errors better than the 16-25 year olds’. To have a probability of success greater than 90%, the childrens’ antibody response would need to be at least \(1.28 \times\) standard errors better than the 16-25 year olds’.

As many have pointed out, it is not uncommon for pediatric trials to be held to a higher standard, often requiring efficacy beyond what is required of adults due to an appropriate caution against intervention in an often vulnerable group. I fully believe that the regulators that requested this had every best intention in doing so. In this particular case, however, this type of threshold can potentially lead to the opposite effect. By requiring the younger children to mount a higher antibody response than the older cohort in order to pass regulatory hurdles, we may be inadvertently pushing towards higher dosing, for example.

It is possible that the choice of 1 was made with the full understanding that the truth had to be better than 1 to pass that threshold with any amount of confidence, but it is important that everyone who contributes to decisions about thresholds understands both the math and the rationale for the choice.

Is this why the 2-4 year old vaccine failed previously? It’s not totally clear since the data hasn’t been released, however based on the tid bits we’ve gotten from media reports, I don’t think so. The New York Times reported, for example, that the 2-4 vaccine only elicited 60% of the response compared to the 16-25 year olds, suggesting that it would have failed by the lower bound criteria alone. So why does this matter? Presumably, these thresholds will be used to compare the post-3rd dose response to the 16-25 year olds as well – does it make sense to require the under 5s to have a stronger antibody response than the 16-25 year olds? Especially with no other option for protection via a vaccine for this age group, I would say no.