Transparency in Public Health

Transparency in public health messaging matters. Hannah Mendoza and I looked at how providing transparent information about why a public health recommendation is being made can increase uptake in a randomized trial published today in Plos One

What did we do?

We conducted a randomized controlled trial to assess whether disclosing elements of uncertainty in an initial public health statement will change the likelihood that participants will accept new, different advice that arises as more evidence is uncovered.

We came up with a hypothetical health scenario and began by asking participants “how likely are you to sanitize your mobile phone?”

(26% said they were likely / very likely)

298 participants were randomized to treatment and 298 control.

controls saw statement 1A, a (hypothetical) recommendation from public health experts that you don’t need to sanitize your mobile phone

treated saw 1B, the same recommendation with added transparent information

After seeing these statements they were asked again their likelihood to sanitize their mobile phone. Then all participants were shown a second, 🆕 statement — this new statement said based on new information public health experts recommend you should sanitize your phone

After seeing these statements they were asked again their likelihood to sanitize their mobile phone. Then all participants were shown a second, 🆕 statement — this new statement said based on new information public health experts recommend you should sanitize your phone

All participants were again asked after seeing this second statement how likely they were to sanitize their phone (this is our primary endpoint ✅)

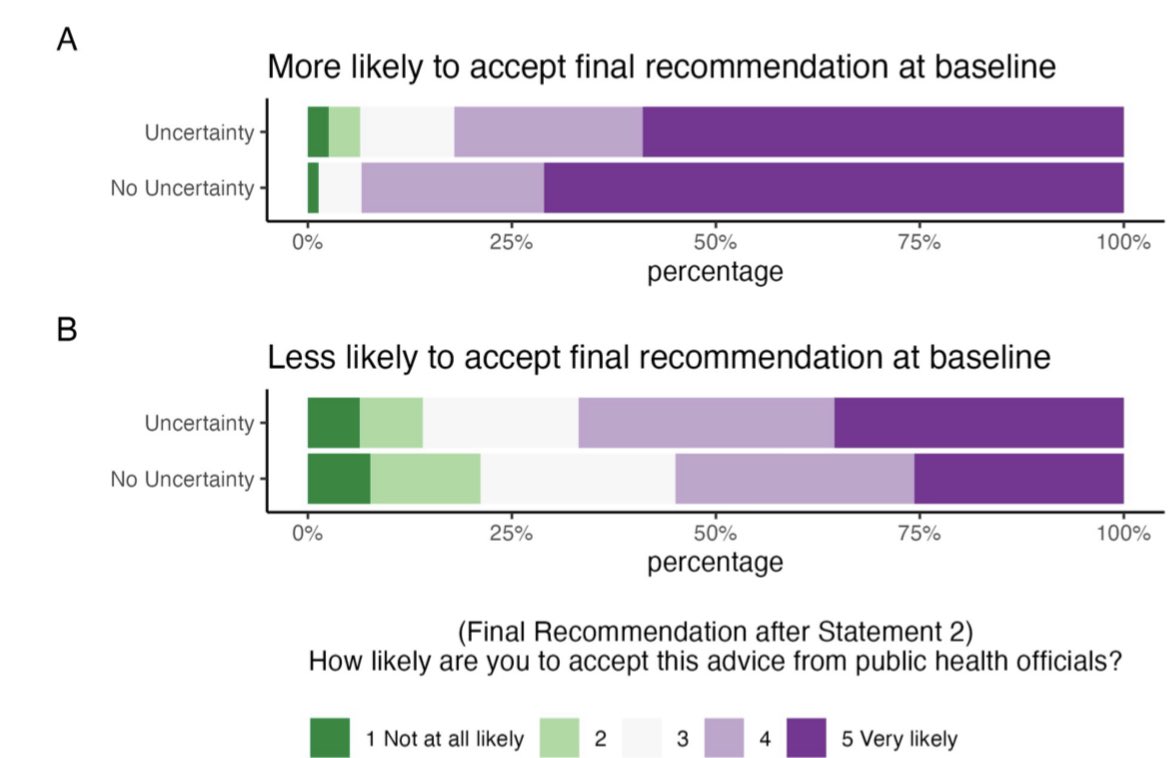

We fit proportional odds models stratified by the baseline likelihood to agree with the final advice.

Among participants who were more likely to agree with the final recommendation at baseline, those who were initially shown uncertainty had a 46% lower odds of being more likely to agree with the final recommendation compared to those who were not (OR: 0.54, 95% CI: 0.27-1.03).

Among participants who were less likely to agree with the final recommendation at baseline, those who were initially shown uncertainty had 1.61 times the odds of being more likely to agree with the final recommendation compared to those who were not (OR: 1.61, 95% CI: 1.15-2.25)

This has implications for public health leaders when assessing how to communicate a recommendation, suggesting communicating uncertainty influences whether someone will adhere to a future recommendation. Presenting public health recommendations with transparency can both ⬆️ and ⬇️ adherence to future recommendations in the presence of changing evidence, depending on the individuals’ baseline likelihood to do what is being recommended prior to seeing the recommendation. Many public health recommendations, particularly those being made during an ever changing pandemic, have a high probability of changing in the future, making this result highly relevant. For example, the recommendation to 😷 wear masks will come and go depending on the prevalence and impact of the infectious disease of concern in the community. When initially communicating this new recommendation to the public, an explanation of the reasoning for the recommendation as well as any potential uncertainty may have resulted in ⬆️ adherence among those who would not have been likely to wear a mask in the recommended settings. 12% of US respondents in March 2020 reported masking to protect themselves. At the time, the recommendation from the CDC was: “If you are NOT sick: You do not need to wear a face mask unless you are caring for someone who is sick (and they are not able to wear a face mask)”. Based on our results, if the initial recommendation to avoid wearing face masks had been presented with the uncertainty communicated, we might expect some of this 12% to be less likely to follow the recommendation — however! 88% were not likely to wear masks a priori; our results suggest this population may have ultimately had higher compliance with the subsequent recommendation to wear face masks had the initial communication been made with transparency explaining the “why” behind it. This study has lots of limitations (it was only hypothetical!) but I think is a good first step for trying to quantify the impact of the way communications can impact future decisions.